When carrying out building surveys in the Birmingham and Coventry areas, one of the things our surveyors will check is whether the house has concrete floor slabs. If it does, they will be on the lookout for sulphate attack damage.

What is a sulphate attack on a concrete floor?

Sulphate attack on a ground floor concrete slab is a very serious problem.

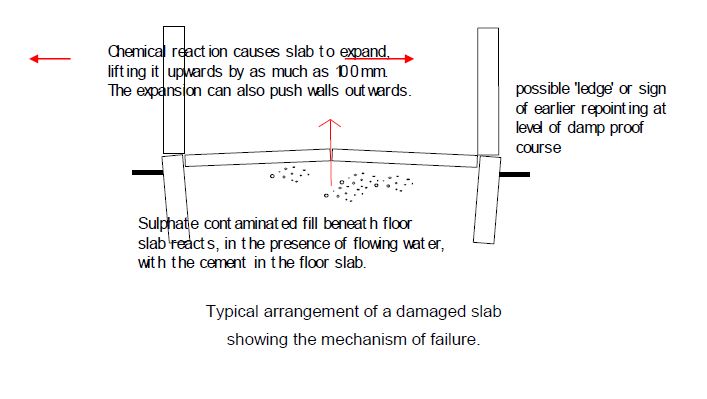

One of the main causes is leakage of sulphates into the concrete floor slab from the material below. Once the sulphates and concrete are in contact, react with each other. This reaction produces crystals, which force the concrete slab the expand. The reason sulphate attack can be so serious is that the expansion of the concrete puts pressure on the external walls, pushing them outwards and destabilising them. The concrete slabs also start to disintegrate, weakening them and reducing their ability to support the building structure.

Damage from sulphate attack can take several years to show up. This is because at first, the extra volume produced by the sulphate–concrete reaction fills up tiny pores within the concrete slabs themselves. It is only once these are full that the concrete becomes lumpy and expansion becomes more obvious.

Which properties do building surveyors consider to be high risk?

Sulphate attack to flooring is a more likely to be problem in post-war properties (i.e. those built between the 1940s and early 1970s) than in houses from other periods.

A timber shortage after the Second World War meant that builders tended to use concrete ground floor slabs instead of the more traditional suspended timber floors. Hardcore beneath the slabs was made up of clinker (broken brick) from demolished houses and furnace ash from industrial processes. Such hardcore materials were cheap and plentiful, but high in sulphates.

Concrete floors in this era also had particularly low cement contents because concrete was mixed on site, with lots of water. This is an issue because high cement content concrete has a greater resistance to the sulphate attack than the low cement concrete used in this period.

Sulphate attack cannot happen without water present to transport sulphates from the hardcore into the concrete above. Moisture can come from ground water or nearby drains or service pipes. A damp-proof membrane between the hardcore and concrete can prevent this (but it should be noted that these can deteriorate and leak, so there is always some risk if high-sulphate hardcore is present). Although supposedly standard practice, damp-proof membranes were rarely used in the post-war period.

There was an extraordinary about of building work in in Birmingham and Coventry following the war, and a scarcity of building materials at that time in these regions. Surveyors are therefore particularly keen to check for sulphate attack risk and damage when carrying out RICS surveys in these areas.

What do surveyors look for during a building survey?

During an RICS building survey, particularly surveys of houses in the West Midlands with concrete floors built during the post-war period in the Midlands, surveyors will be looking for signs of sulphate attack. These include:

- heaving and cracking of the floor

- lumpiness or doming of floors

- traces of white salts on the floor surface

- expansion of flooring at the damp-proof course level, pushing the outer brick walls sideways

- lateral movement of brickwork

- stepped diagonal cracks in external walls

- moisture rising through the top of the floor because of the concrete’s reduced strength and density.

Surveyors may comment on the risk of attack, even if the signs of attack are not evident. If a property is in a high-risk area, has a concrete floor and was built between the 1940s and early-1970s, it is at high risk. This is especially true of local authority housing, which at that time was built quickly and cheaply.

The later the property was built during the post-war period, the lower the risk. This is because building techniques were gradually improved – hardcore was chosen more carefully, and damp-proof membranes and sulphate-resisting concrete were more likely to be used.

Surveyor recommendations for properties at high risk

If sulphate attack is suspected, or the house is thought to be at high risk, the building surveyor will recommend an invasive sulphate test. This will involve excavating a trial hole to assess the condition of the concrete, determine what type of material is below the concrete and find out if a damp-proof membrane is present. Concrete and hardcore samples will be tested on-site for moisture levels and in a lab for sulphate content and cement levels.

Even if sulphate attack has not occurred, if the concrete tests show that it has a cement level lower than that needed to resist attack, and the material below has a high sulphate content, replacement of the floor slabs and potentially the hardcore below may be recommended to prevent structural damage in the future. This is particularly likely if there is no damp-proof membrane. For example, if a water source becomes present in the future e.g. leeching of water from old clay drains, then the property could be at risk.